Caged Birds

Justin T. Andries

When I realized that I was a black man living in a white man’s world, my whole perspective of life changed. I saw everything from a different point of view. I paid attention to black people in positions of power, black people who were wealthy, and even how black people were depicted to society through the media; whether that’s on the television or in a museum. More importantly, I saw myself from a different point of view. I knew that I had to work twice as hard as my white counterparts. I knew that my skin was a few shades darker than the standard of beauty in this world. I knew that there will always be a target on my back because some of my counterparts are still not used to seeing a black man free from the chains his ancestors cast upon mine.

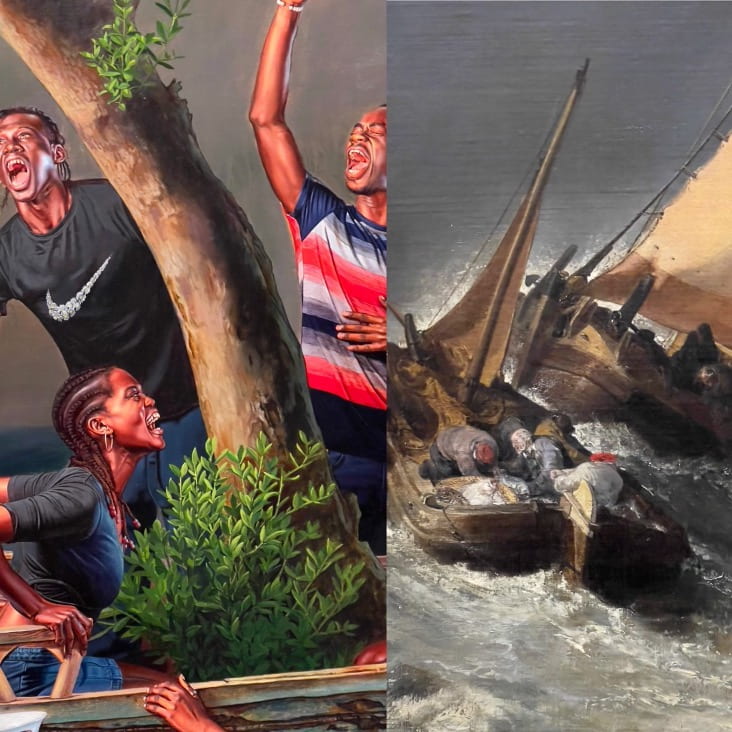

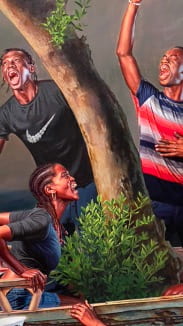

It felt like time stopped when I stepped into Kehinde Wiley’s exhibit at The National Gallery. His talent left the room so silent and in awe that I could almost hear the paintings breathe. I saw myself in his paintings. I saw struggle, hardship, pain, and triumph. But more importantly, I saw blackness – something most art exhibits lack greatly. Wiley, who is an American artist best known for his presidential portrait of Barack Obama, reworks white history in a contemporary way. Wiley speaks to people of color and depicts just how valuable they are by replacing important white historical figures with “ordinary” black people (quotes because there is nothing ordinary about being black). One painting that caught my eye, yelled at me almost, was a portrait of six individuals (four on a boat and two trying to get back in) who appear to be in the midst of a storm. Not one of their faces were similar, not one of their faces were telling the same story. All of them were asking for help. You could see two of them pleading for anyone that may be around them (the man in the Nike shirt and the women with the black t-shirt) while the two outside the boat were asking to be saved from the clutches of the deep blue. The last two were pleading for God. You can almost feel the strain of their voices and see the pain in their eyes as they approached death faster than they ever anticipated. The more I stared at this painting, the more detailed it became. I am still in awe of this portrait.

You can tell Wiley appreciated the artists he was mimicking while he gave life to these old nineteen-century paintings. His use of more vivid colors and symbols were attractive and compelling. Comparing the portrait above to the original by Joseph Mallord William Turner, one can see how Wiley gave an identity – a soul – to the individuals on the boat, depicting how life is precious especially when one is on the glimpse of death. Wiley focuses more on the individuals rather than the storm itself which speaks volumes in terms of how race is depicted in America. Institutions are deeply embedded in race and fail to see black people for their worth, for their individuality which confines them to boxes with labels that we may never seem to get rid of. We must escape the cage of whiteness and race as it is constructed and free the ones who have been stuck in this never-ending storm of hatred and discrimination. When I look at Wiley’s paintings, I feel free.