The True Horrors of WWI Through Art

Giovanna Grizotte

Last week, our DWC class went to the Tate Britain for a guided tour of World War I art by Lucinda Hawksley. The tour guide began by showing art leading up to WWI, but once we arrived in the WWI exhibit, I couldn’t help but notice that most of the paintings were similar; the paintings did not shy away from capturing the gruesome and horrifying nature of war. Throughout our DWC course so far, we have read many texts regarding war and its effects on society, so the art I viewed brought these texts to life, allowing me to further my understanding that war is far from pleasant.

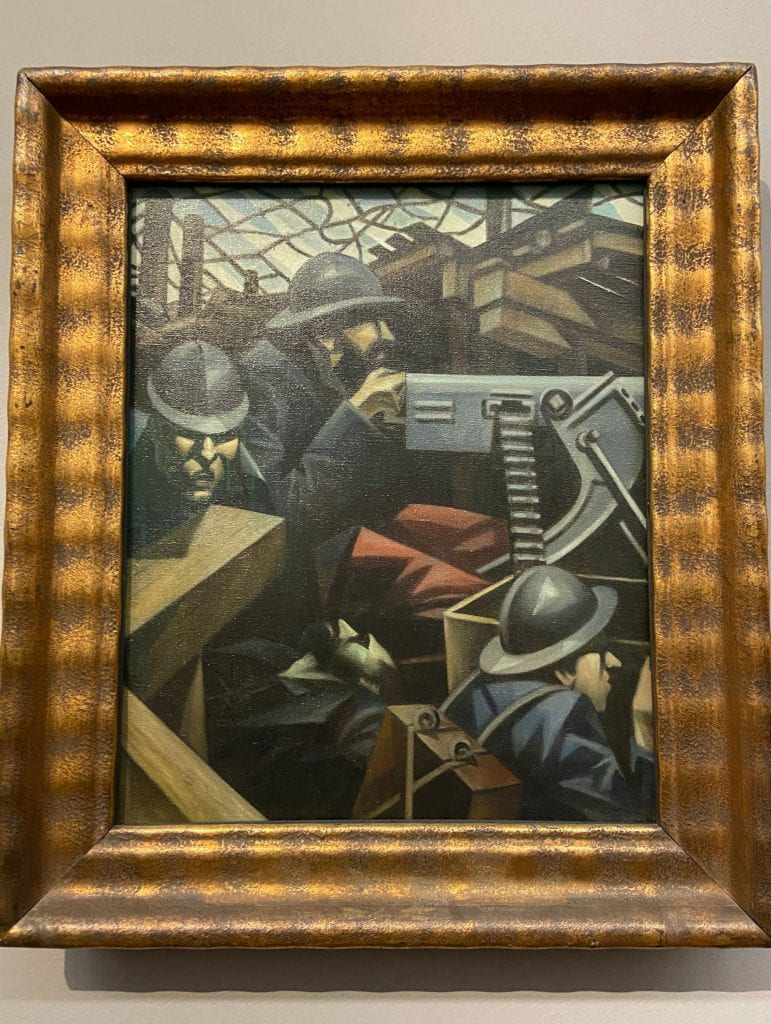

One of the first paintings the tour guide showed our group was Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson’s La Mitrailleuse from 1915. She also mentioned that Nevinson was physically present in the trenches, drawing his reality. He wasn’t fighting, but he was observing the barbarism and depicting it for those at home with no concept of combat. I have seen war art before, but I figured the artists drew from their imaginations or from other accounts, so it was surprising to hear Nevinson truly captured what he saw first-hand. His painting La Mitrailleuse is one that I will remember forever. The painting incited an uneasy feeling in me because it is uncommon to see humans depicted as machines. The artist implements cubism into his work, making the soldiers look inhuman as they mold into the machines they are carrying. Although the painting is eerie to look at, Nevinson’s choice of style is significant because it proves his point that war dehumanizes combatants.

Another painting with a similar take on war as Nevinson’s painting is Mark Gertler’s Merry-Go-Round from 1916. After seeing Nevinson’s painting, I thought nothing else could make me feel worse until I saw this painting. A merry-go-round is commonly associated as a children’s amusement ride. It was eye-opening to see a ride I related to a happy childhood memory illustrated in such a dark way. In our readings, we have learned that young children were involved in war efforts and in Peter Cooksley’s The Home Front: Civilian Life in World War One, he discloses that Boy Scouts served as coast guards during WWI. Now, I see why it was important to use the merry-go-round not only for its symbolism of a never-ending cycle of war, but as a childhood ride as well. Children and war should not be associated, yet they were and still are.

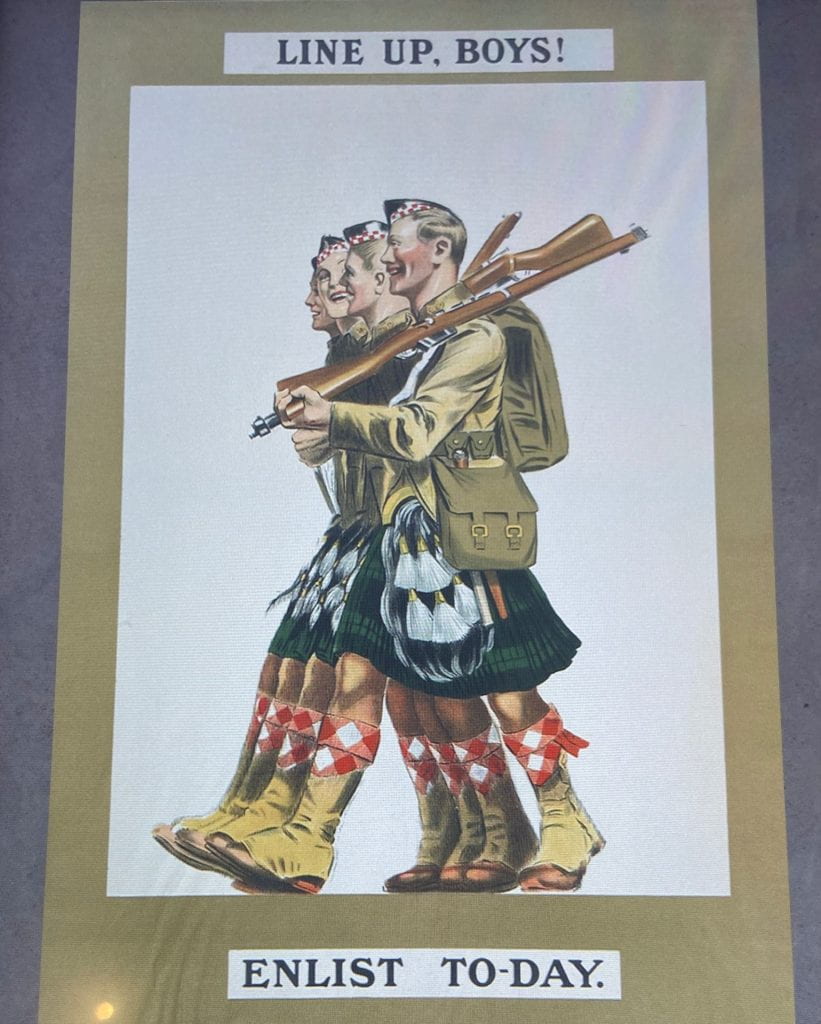

After I viewed this piece of art, I recognized that children and adolescents have become puppets of war. A carousel which should be enjoyable for youth, is portrayed as terrifying in Gertler’s work. The soldiers in the paintings all have the same frightening expression and are trapped in the continuous, agonizing cycle of war. This painting is significant because it contradicts the First World War propaganda that was shown to young boys to get them to enlist for war. Many times, propaganda posters pictured young, happy boys participating in war to persuade the audience. When young boys joined the war, they were faced with different experiences, completely opposite of what posters showed. For example, this “Line Up, Boys!” poster by W.H. Caffyn in 1915 paints war as delightful and aesthetically pleasing. The artist is aware that boys who viewed this poster would envision boys their age as happy warriors defending their nation and influence them to enlist as well. Although, many soldiers were emotionally, physically, and mentally affected by war— something propaganda failed to showcase.

Therefore, I like how real the art at the Tate Britain is. It captures the harsh reality of World War One and does not try to fool people in the way propaganda did. Both the paintings from Nevinson and Gertler show the actual side of war, a narrative many people at home had not seen nor experienced, but it is one that had to be shown.