Art in its Many Forms: The Tate Modern

On my second weekend in London, per a recommendation from Dr. Boeninger, I decided to visit the Tate Modern Museum. Joining me were new friends from various Universities that I had met in my first few days at our dorm, the Stay Club. The Tate Modern was bursting with incredible artwork in many forms, the first of which I saw upon walking in the massive entryway. Floating through the air above me were jellyfish-esque sculptures with moving tentacles. The mystical nature of this exhibit, how these were able to float seemingly on their own (propelled by tiny fans) and the melodic way that they bobbed up and down was the perfect greeting to the museum, and one of my favorite parts.

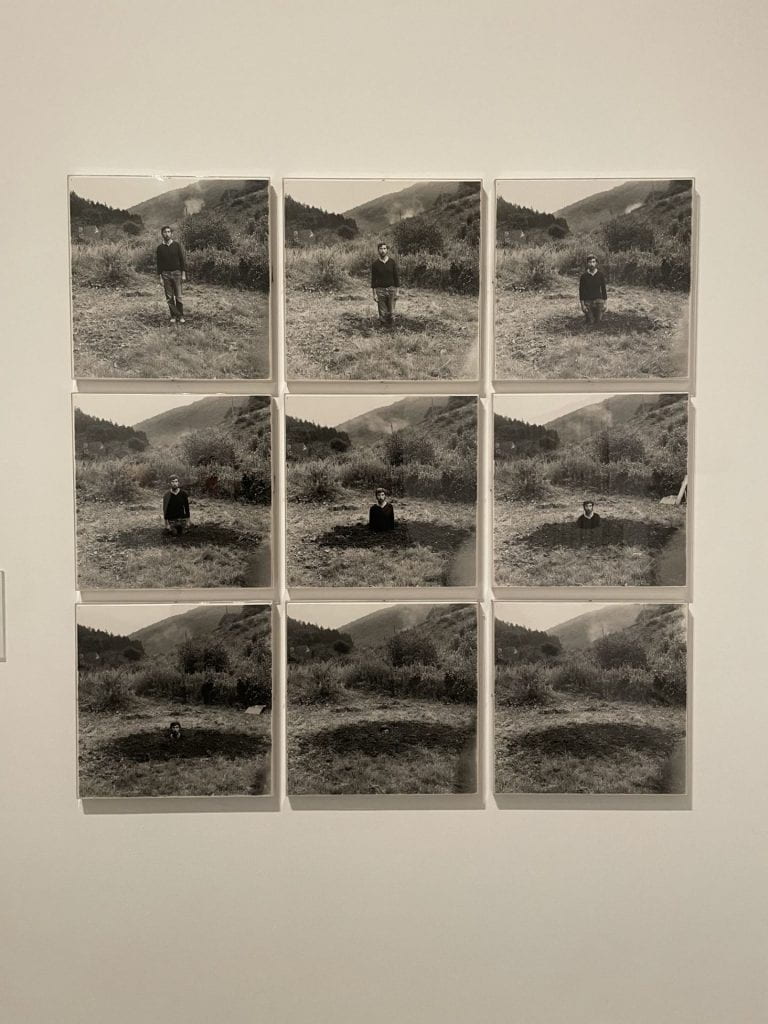

As I continued upstairs through the rooms and exhibits, I was impressed by the vast range of art displayed, from painting to photography to film and sculpture, with exhibits commentating on the colonization of Australia, photography depicting human impact on the environment, and the strong messages of the Guerrilla Girls, a group of artists fighting racism and sexism in the art industry. I particularly enjoyed a photography display entitled “Self-Burial (Television Interference Project)” by Keith Arnatt in 1969. This was a series of photographs of a man burying himself. The description beside the photographs told me that on German television in 1969, one photo from the series would appear each day for about 2 seconds, interupting a normal broadcast, with no explanation. The messaging behind the piece was a reference to how artists, like their art, disappear over time. The strangeness of the photos, as well as the way in which they were originally presented in 1969 struck me, and even seemed a bit comical.

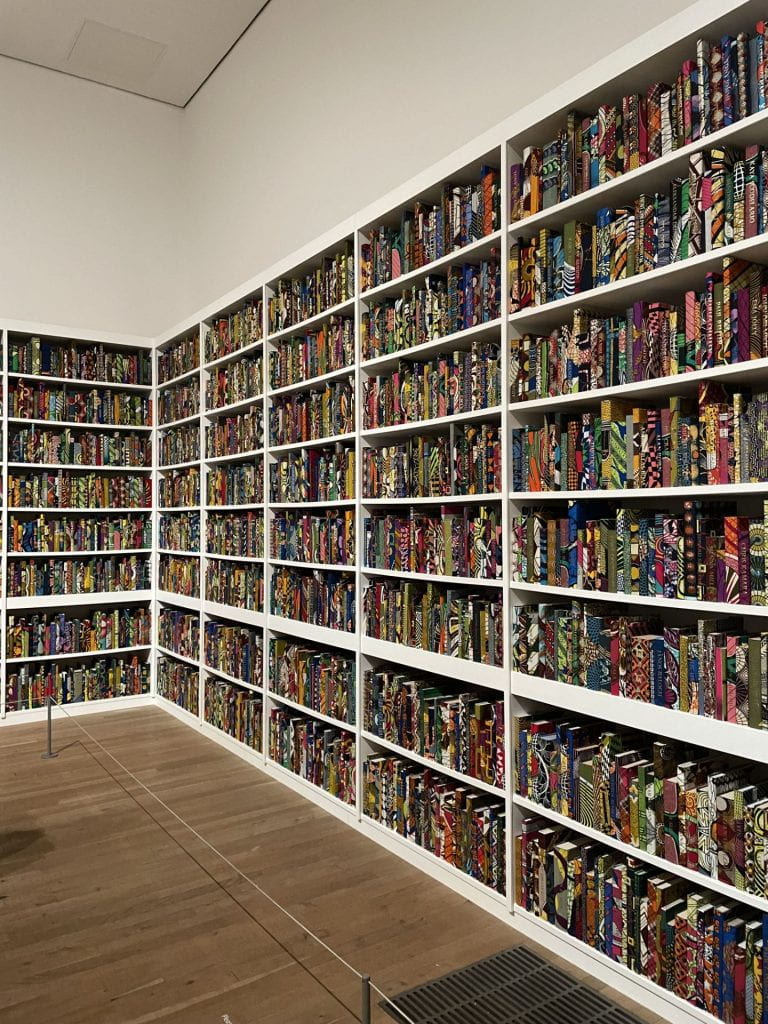

The exhibit that struck me the most, however, was titled “The British Library” by the artist Yinka Shonibare CBE. This exhibit caught my attention because of the bright and eye-catching colors incorporated. At first glance, the room appeared to be brimming with books encased in beautifully colored fabric. Confused by what the message behind the artwork was, I read the description. Here I learned that Shonibare is a Londoner native to Nigeria whose background influences much of his work, including this one. 2,700 of the over 6,000 books included in this exhibit bore the names of first or second generation British immigrants whose societal contributions may or may not have gained recognition. What I read next intrigued me– that some books bore the names of people opposed to immigration, creating a tension within the exhibit that is something real and faced in the world by immigrants every day. Some spines remained blank, an acknowledgement that immigration is an unfinished narrative. The books are encased in African Wax Print fabric, a nod to colonialism’s link to cultural appropriation, as Dutch colonizers produced cheaply made fabric in an effort to recreate the beautiful patterns in African fabrics, which were in turn absorbed into Western and Central African culture.

This exhibit was so dynamic and contained so many dimensions. No part of it was an afterthought, but every aspect thought through and purposeful. It represented a challenging subject in such a beautiful and creative way, and the message stuck with me. The Tate Modern was home to so many unique and powerful displays of art, and definitely something I recommend to anyone visiting London.