Call Her Asase Yaa

Emily Cabreja

Museums are white. White ceilings, white floors, White people.

Art museums are usually the whitest of them all. Paintings of long, wavy strawberry-blonde hair wisps gently across the unwrinkled, pale forehead of a fair and thin-lipped maiden. Her company are other white bodies, dressed in dyed silks, the light catching on their multi-colored jewels which shine onto foreign fur coats. Some are smiling, others are looking at the small animals running across the court, and all are white, white, white, whiter.

Fun is for them, beauty is for them, Black bodies are theirs to conquer.

So, I never find myself in museums, or at least not in the way that I want to be. I am not one of the royals or intellects, I am not a friend to nature or people—I am a servant, the jester, the shadow.

In London, The National Gallery is no different from the other museums that I have visited, with the exception of carrying Kehinde Wiley’s exhibit The Prelude. Wiley is a contemporary painter and is best-known for taking paintings from the Romanticism era and twisting them by placing modern Black subjects (usually chosen by Wiley randomly on the street) in the original paintings.

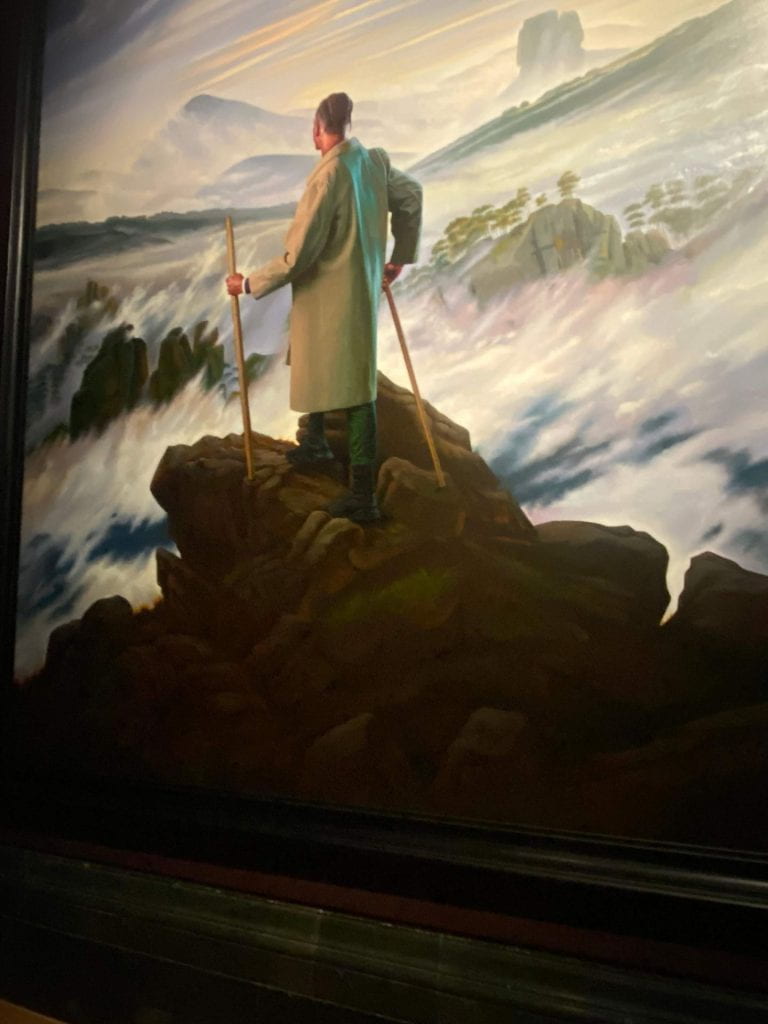

I recall taking a breath of relief when I entered The Prelude for the first time after walking past hundreds of pieces depicting the same bodies and subjects. Here, there was a person of every shade of black and brown being brought to life on a canvas, surrounded by nature wearing clothes from the 21st century. The subjects in the paintings felt familiar and real, and while I found myself enjoying all the pieces, the one which captivated me the most was Wiley’s Wanderer above the Sea of Fog.

The painting shows a young Black man standing on the edge of a rocky cliff, his body is faced away from the audience as he looks into the sea of fog—entranced, victorious, powerful. He is wearing dark jeans, black sneakers and a gray trench coat, his hair is braided and carries only two hiking sticks, and at that moment, he is one with nature.

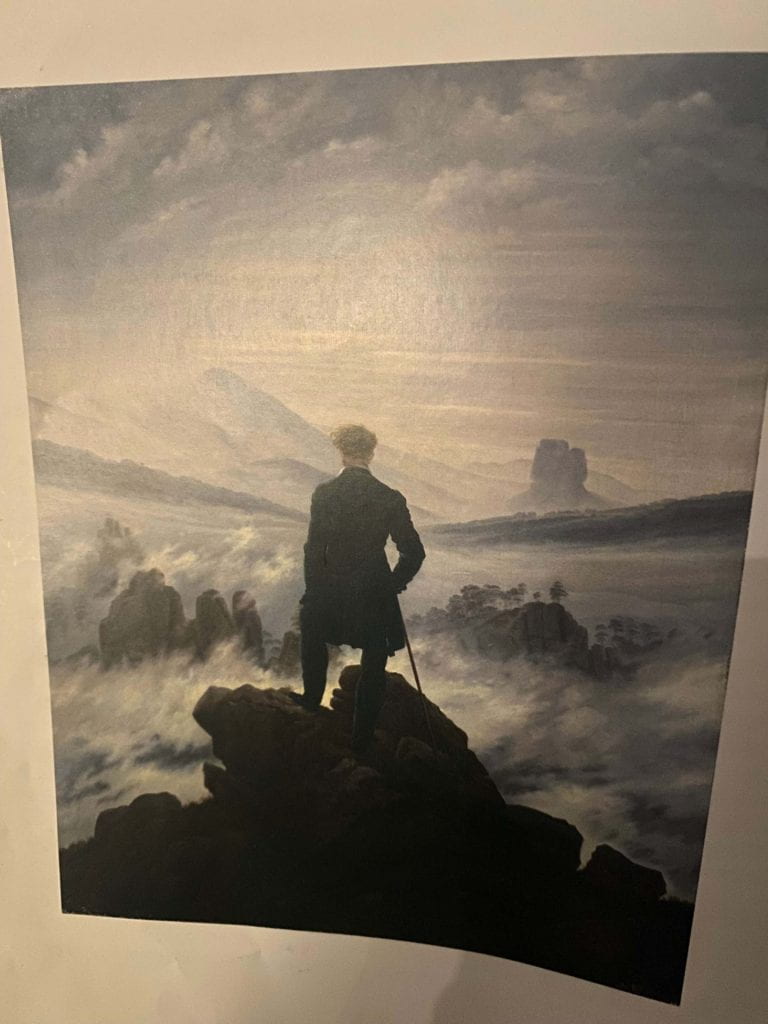

When putting the paintings side by side, Wiley’s art is clearly inspired by Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer above the Sea of Fog. The landscape presented to both young men are the same in grandness and presentation, however, the human subjects capture different elements of man’s relationship with nature. Wiley’s subject stands facing the sun, his face is kissed warmly by the sun while his back is dark with shades of black and blue. This man is both away from the audience but close, his figure is the focal point of the painting which draws you in. Wiley’s subject is one with landscape but also together with the viewer, attempting to bring you into the moment with him. Friedrich’s subject is far away from the audience and his face cannot be seen, but his pale neck shows clearly against the outdated dark clothing, along with the wispy blond hair sticking out against the blue-silver sea. This man is a conqueror, he is away from the audience and drawn in fully into the sea before him.

Humans painted into nature have a specific relationship with their surroundings— there is either harmony or chaos. However, historically art has made clear who can enjoy (or fear) such a relationship with nature, and these are often people who bear no resemblance to me. Wiley’s art strips the barrier away completely, allowing Black and brown people to see themselves memorialized with and within nature.