Colonialism Through Artifacts

Kenny Solosky

This week, I visited the British Museum’s room 25, which includes plenty of artifacts from many different African countries, dating back thousands of years. Two artifacts that stood out to me include the brass head of the king of Ife, Nigeria, which dates all the way back to the 1300s and early 1400s, and a textile commemorating Julius Nyerere, the president of Tanzania who played a large role in separating from Britain. By comparing these two artifacts, we can see how British imperialism impacted African culture over time.

The brass head of a king was accidentally found in 1939 by builders in Ife, and they were able to identify that this comes from the great city-state of Ife that was most powerful from 1100-1400 AD.

This city-state was very important to both long-distance and regional trade during the time, which allowed it to flourish. There is some red paint that still remains on the crown, which is incredible considering how long this artifact has been around. Even though there is little known about the brass head, one thing that is certain is that it represents a king. Plenty of cities in Africa did just fine without British intervention. Empires such as the Mali Empire, Songhai Empire, and the Ife empire were known to be incredibly strong. Timbuktu, a city in present-day Mali, at one point was the center of one of the most prosperous trading empires of all time. Another thing to notice is how the crown represents the customs and traditions of African culture at the time. Art in Ife consisted mainly of works in brass, copper, stone, and terracotta. The brass sculpture represents the prosperity of the empire, for this sculpture in particular is seen as one of the greatest achievements of the empire. This artifact is a great representation of African culture before British imperialism.

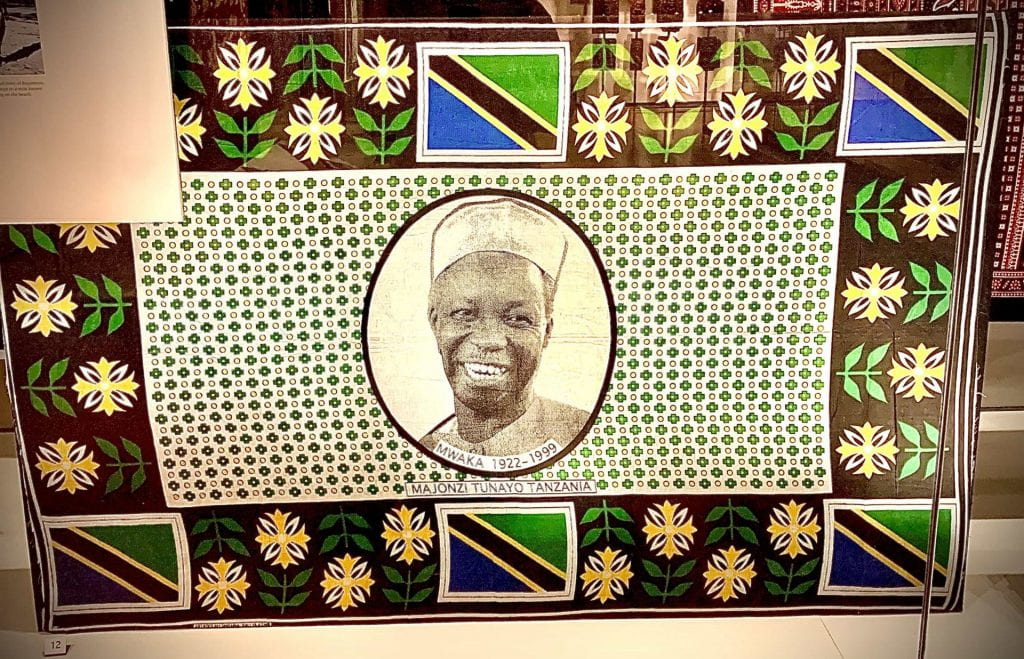

The textile, on the other hand, represents African culture after the period of British imperialism .

The man portrayed on the textile, Julius Nyerere, was an anti-colonialist who, as mentioned before, was a major player in the independence movements of Tanzania. He gained the respect of those who worked with him because not only was he able to lead an independent Tanzania, but he was also able to keep the nation stable and unified. This textile is known as kanga, which is a locally produced product that has certain inscriptions in the Swahili language that are meant to send a message. I noticed a few about health and sexual relations, including a textile that referred to the AIDS crisis, religion, and politics, as seen here. The message under the picture of Nyerere reads “majonzi tunayo Tanzania,” which translates to “all of Tanzania mourns.” Another interesting thing I learned is that these textiles were imported from Europe, the far east, and a few other spots, which shows how African customs and traditions were even taken over by their colonizers. However, after a little bit, they started making these textiles once again.

These two artifacts are similar in the sense that they both pay tribute to a hero of their time. They are both leaders; however, they differ greatly. The king was a royal leader who controlled a great empire, while Nyerere lead an independence movement and was able to maintain a stable country afterward. The brass head of the king has a feel as if we are not on his level, while the textile makes it seem like Nyerere was a leader for the people. In the 1300s they were making tributes for those who led empires, while in the 2000s they were making tributes to those who broke away from empires.

Lots of museums in Britain tend to ignore how poorly they treated their colonies. They ignore horrible events like the Mau Mau Rebellion and other instances where they treated the colonized poorly. The British Museum, however, has artifacts directly from Africa that help us understand how the colonized really felt about British imperialism, which allows us to look at this period from a different perspective.