Forever Remembering Conflict Through Art

Giovanna Grizotte

One of the main themes we have been focusing on this semester is how war should be remembered and particularly if conflicts regarding the British are remembered in England or brushed aside. While visiting the Tate Modern, these questions of how conflict should be remembered remained in my memory. In our DWC class, we have recently learned of two conflicts regarding British occupation: the Mau Mau Rebellion and the Irish Troubles.

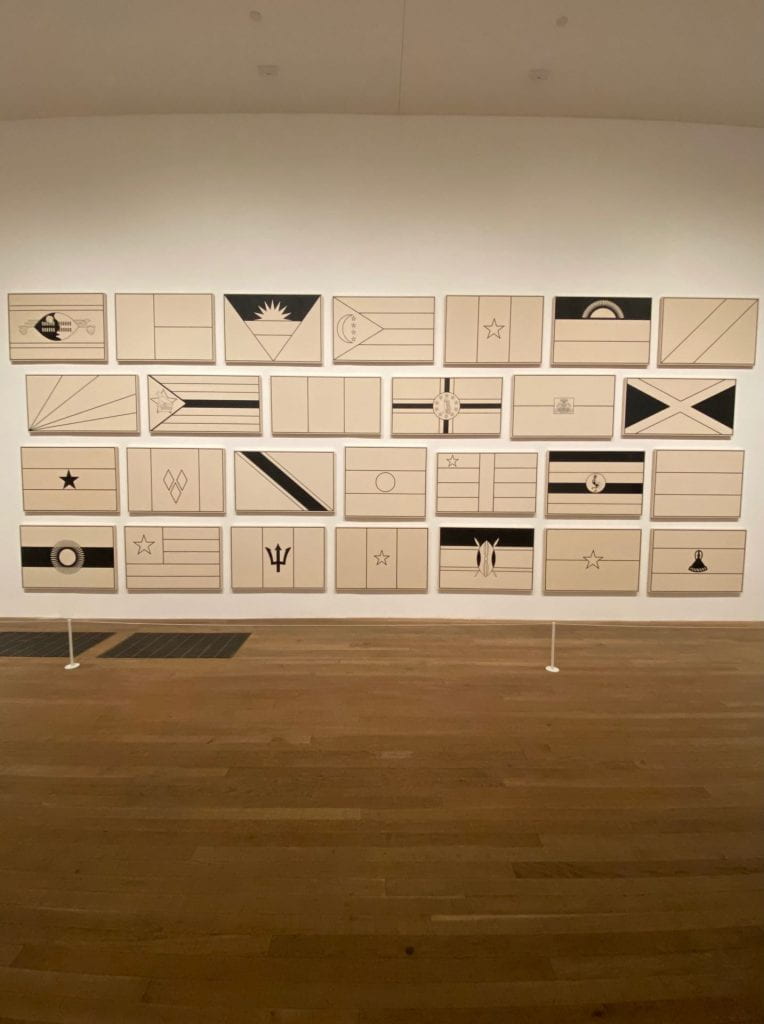

In the Artist and Society exhibit at the museum, I was met with multiple works of art from artists displaying their perceptions and experiences of different conflicts. One of the first and largest works in the exhibit I saw was Fred Wilson’s 27 flags of African and African Diaspora nations.

This piece reflects on the countries that were formed because of independence movements and freedom from British and European colonial rule. The first aspect of the work that caught my eye was the lack of color on the flags. Upon reading the description on the side of the artwork, I learned that Wilson is demonstrating how the flags have been stripped of their colors in the same way many African countries were stripped of their identities through colonialism. By removing the colors, Wilson is also questioning if the flags can accurately represent the complicated history of the nations. He says, “the colors can represent tribal, cultural, religious, and political identities as well as national ones, sometimes simultaneously.” Since the colors on the flags are essential to African identity, Wilson makes a strong message that these nations were denied the ability to distinguish themselves and be unique; through his use of black and white color representation, Wilson shows both complexity and duality.

Wilson’s artwork reminded me of our studies on the Mau Mau Rebellion, in which the Mau Mau fought back against the British empire because they wanted independence from the British. The uprising took place in Kenya and that is one the countries that is a part of Wilson’s work. This piece of art evokes sadness in me because British and European colonial rule deprived these nations of their identities. Although this artwork made me sad, it was good to see that these nations are still being remembered to this day. In many other London museums, the British try to portray themselves as neutral, but the description relating to this piece directly calls out the British for their colonialism. Wilson’s art differs from other war art I have seen because a lot of the earlier art relates to actual combat and the effects of war on soldiers, whereas this piece shows the impact of colonization on African countries.

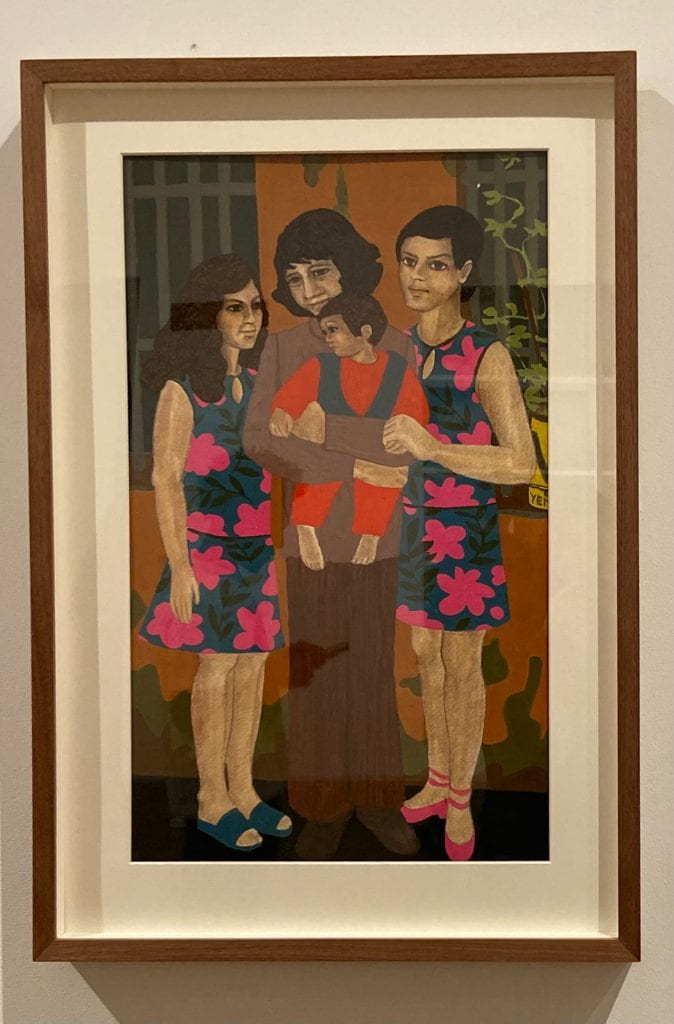

Another piece of work that stood out to me was the Prison Paintings 1972-8 by Gülsün Karamustafa. Karamustafa is a Turkish woman who was imprisoned after the Turkish military coup of 1971. These paintings demonstrate daily struggles of the women in prison with her and show a range of women’s identities as mothers, wives, friends, and prisoners. The artist painted this work after being released from prison in order to remember what had happened. The two paintings that drew my attention was one with three women and one of them is holding a child and another painting of a woman in a jail cell with a Turkish double teapot beside her. (insert Grizotte #2 and Grizotte #3)

I focused on these two because they reminded me of the roles of women during the Irish conflict where some women were imprisoned, and others protested for peace.

In “Ruffling a Few Patriarchal Hairs: Women’s Experiences of War in Northern Ireland,” from the Cultural Survival Quarterly Magazine in March 1995, the article mentions the Peace Women and women prisoners. The Peace Women emphasized that women were unified by their roles as mothers and that their “mothering nature …was contrary to violence” (3). Karamustafa’s painting of the women and the child in one of their arms reminded me of the Irish Peace Women who opposed violence. I related Karamustafa’s other painting of the woman in the cell to the Irish women prisoners who striked by refusing to wash themselves for a year to “protest the assault by prison guards and lack of political recognition” (10-11). Both the Turkish and Irish women faced similar struggles and I had not seen art of women imprisoned at any museum so far, so this painted a clear image in my mind of what these women faced. This art piece evoked sorrow in me because I can see the despair in the faces of the imprisoned women, and it hits hard after learning that many women prisoners were assaulted. Both Wilson and Karamustafa’s art feel so real to me and after viewing them, I understand why it is so important that art relating to past conflicts should forever be remembered.