Memorials: Does Size Add Significance?

Georgia Flynn

This week as we toured Westminster Abbey, I kept the theme of memory in the back of my mind as I looked at the memorials and graves of thousands of people. One thing that struck me was the many large memorials complete with statues and inscriptions commemorating people I have never heard of. While I thought this was maybe due to not growing up in the British school system, our tour guide informed us that essentially nobody has heard of these figures. Burial in Westminster Abbey used to be based on not strictly merit, but how much someone was willing to pay. Large extravagant memorials were a status symbol, something not earned, but bought. This contrasted with figures such as Jane Austen, renowned and legendary by modern standards, being commemorated by merely a small stone and a simple engraving of her name. Charles Darwin, taught in classrooms around the world for his discoveries in evolution, yet remembered by an easily overlooked unassuming stone.

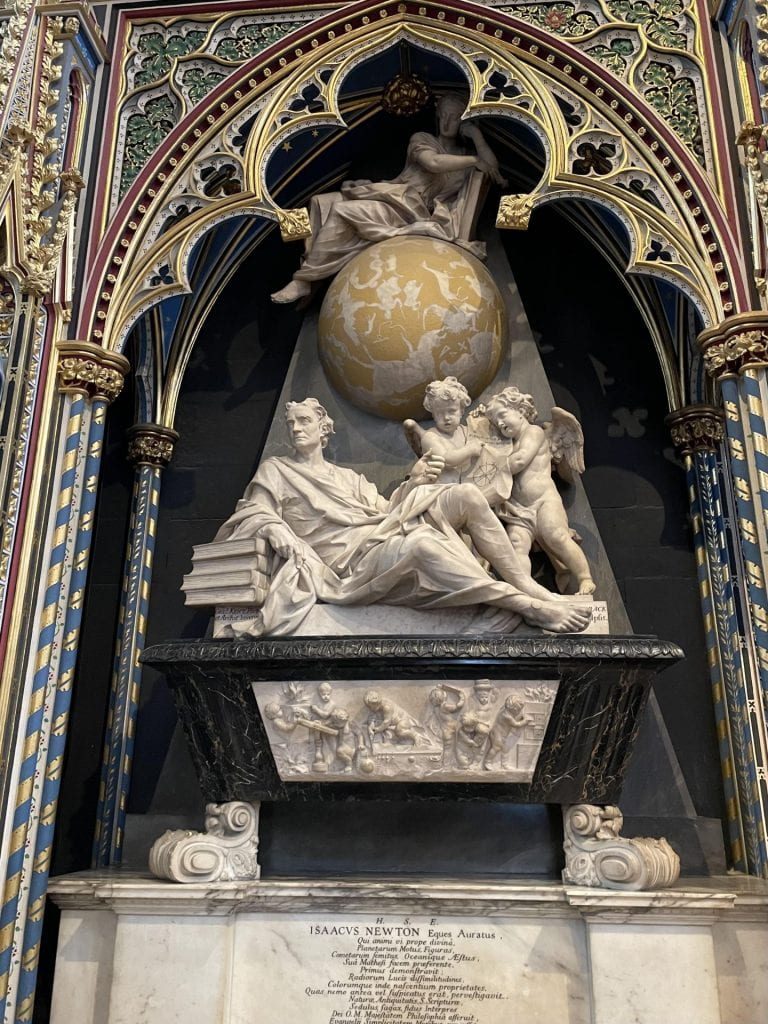

This begs the question: how do we remember people, and why? If men of status in their day can afford a front and center space and sizable memorial but still (much to their chagrin) fade from public memory, it is not money or material things that make people memorable. A memorial does not make the subject memorable, but rather who the subject was as a person. It is not the material aspects, but the actions of the person and the contributions that someone made to society. Figures become timelessly relevant by their works and their discoveries, not their ability to make a physical memorial for themselves. Memorability is earned, not bought. Some figures, however, have both a large memorial and timeless memoriam, such as Isaac Newton and William Shakespeare. This shows that meaningful contributions to society and wealth of someone (either themselves or a benefactor deeming a large presence of them in the Abbey necessary) are not mutually exclusive. However, wealth and status does not equal memorability. This consensus is still relevant to this day. While people of wealth and means can certainly be well known figures in their time, it is people who make meaningful contributions to society that are remembered steadily.

As we moved on from the politicians, authors, scientists, etc. in the Abbey into the royal figures, there was another noticeable change in the memorials. The names of royals from eras gone by all seemed to run together as our tour guide pointed out various graves marked unassumingly in the black and white tiles of the floor. However, the more renowned and famed monarchs such as Elizabeth the First and Mary Queen of Scots were set apart in their own rooms with extravagant and large memorials.

I saw these as almost opposite to the other memorials, where for the most part ( and with exception, of course), merit and public opinion of a royal figure determined the extent of their memorial. Royal figures’ memorials represented extreme examples of what I saw in other parts of the abbey– impressively extravagant versus diminutive and simple. This visit made me wonder how different the Abbey would look, for both royal and non royal figures if the size and extravagance of the memorials was based soley on merit rather than money and influence.