Romanticism through new lenses

As a little girl who immigrated from Latin America to the United States, I always viewed art in a different manner. Until I was seven years old, I had grown up surrounded by art that involved individuals who looked like me, and similarly, were also drawn by individuals who looked like me. Yet when I arrived in the United States, I soon began to feel as if art was simply reserved for one kind of individual. Everyone in creative spaces, whether it be the media or historical paintings around school and in my textbooks, all looked the same. As time went on, I had become accustomed to the demonstration of white individuals being held to a higher status. They were portrayed in a much brighter light than the few people of color I could pick out in these pieces. They were the heroes. The saviors. The wealthy and educated. Whereas the individuals of color were always portrayed as the white men’s servants, or as criminals trying to immigrate to a different country to cause harm. I did not look like them nor did they resemble the stories of the individuals I knew, but I never really questioned it. At least not until once again, I moved to a community of people that mostly all looked like me. Why did I never identify my friends, my family, or myself in these art pieces?

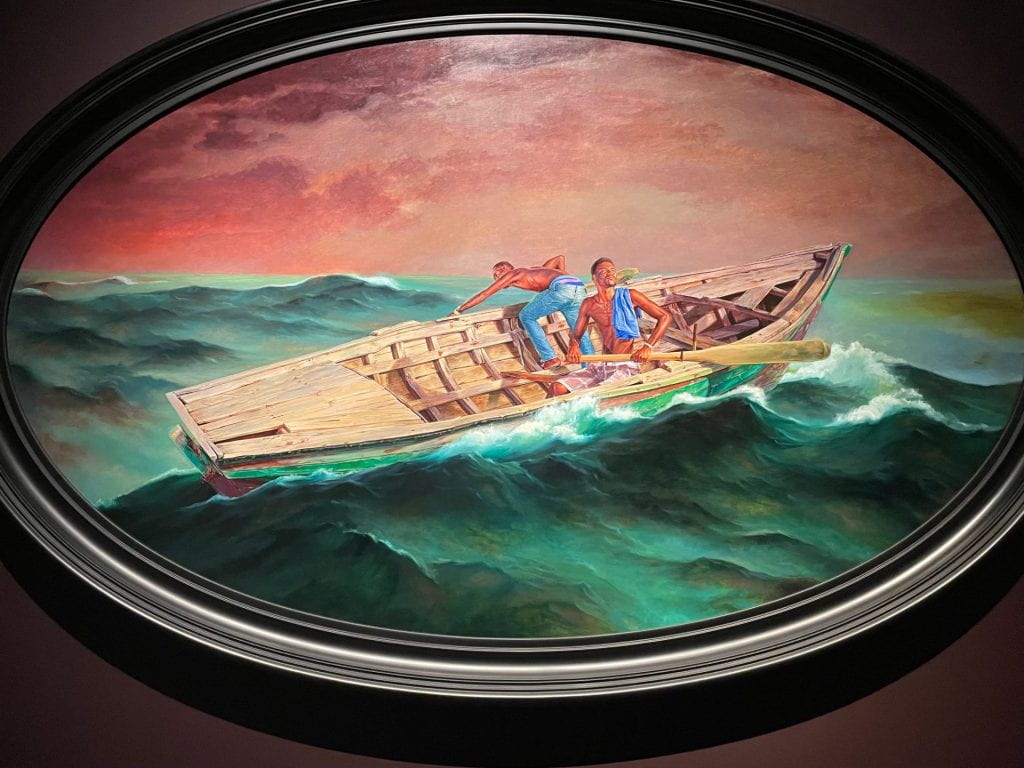

This question has always lingered in my mind, but it was not until I explored Kehinde Wiley’s exhibition The Prelude that I recognized the true meaning and importance that representation holds. In learning about European culture, the same pattern of the faces of white men and women on the walls continued. These pieces tell much history, but I could not help but think what part of history was being left out. The two paintings that caught my attention were Kehinde Wiley’s “In Search of the Miraculous” and Sir Henry Raeburn’s “The Archers.”

Although these two pieces are portrayed in different settings and circumstances, the biggest connection between these four men is the trust that the two men in each picture exhibit. The man holding the bow and arrow and the man that is looking beyond the horizon behind the second man’s back both represent safety and brotherhood. They are protecting the men that are looking forward, as they have probably taken a leadership part in their journey. All four of these men depict the essence of bravery, solidarity, and passion. The bravery of finding a way out in hard times. The solidarity in trusting one another, even in the midst of the storm. The passion of facing the unknown head on, even with fear in one’s eyes. The brighter color shades further on in the paintings despite the darker shades at the front of the paintings serve as symbolism of the gleaming future that will come after the disturbance has passed. All these features combined serve as a reminder that being able to view life struggles from the lenses of individuals look like us inspires us to recognize that if our people could face adversity and persevere through it, so can we.

Through his modern twist on Romanticism, Kehinde Wiley provides hope to individuals of color. Hope that the experiences we encounter day in and day out will one day be displayed, accurately. Hope that one day seeing Black, Latino, and Asian faces on art pieces is no longer a foreign concept. Hope that representation in literature, art, or architecture progresses as time goes on so all individuals can feel seen in a world full of valuable history.