Unexpected Memorials

London is a city filled with memorials: to politicians and artists, soldiers and heads of state. The most famous loom over areas of the city and become sites of pilgrimage, like The Cenotaph on London’s Whitehall Street. A large part of our class this semester will involve thinking about who we choose to remember and how we remember them. We’ll be asking how and whether memorials work, and where they should be placed. We’ll be visiting and discussing many famous memorials, imposing structures or thought-provoking art pieces.

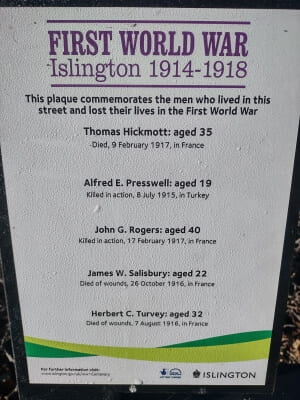

But one of my favorite experiences is coming upon a memorial in an unexpected place or to an unexpected person. I had two of those moments this week in my rambles around London. One happened on the corner of the quiet street in Islington where my family is lucky enough to live this semester. I’d walked past the street sign perhaps two dozen times before noticing a small plaque posted on it, really not much more than a laminated sheet of cardboard.

To my surprise, the uninspiring plaque was a WWI memorial. Not a general one to the hundreds of thousands of British men who lost life or limbs in the War to End all Wars, but a simple list of five men from this street who gave their lives in the conflict. Somehow, the very local and small scale nature of this memorial made it more powerful. How is it possible that families on this street lost five soldiers in four years? Imagine what it must have been like to watch one neighbor after another leave for war and not return. One of them was someone’s teenage son. Two others were likely family men, aged 35 and 40. Our street is not a long one, so it is hard to imagine so many men dying from one street. It turns out, however, that the park across the street used to be the Beaconsfield Buildings, built in 1879 to house thousands of working people. By the time of the war they were overcrowded tenements. When they were demolished in 1971 they were considered the worst slums in Islington. These men who gave their lives were likely poor, used to crowded and substandard living conditions but still utterly unprepared for the muddy trenches of France.

The second monument that made me stop in my tracks this week was in a more expected place, a crypt. One of the most interesting cafes in London is the Crypt Cafe, a thriving business selling soup, scones, and sausage rolls underneath the church St. Martin in the Fields, the lovely church on the corner of Trafalgar Square.

As we enjoyed our delicious food and hot beverages, we began to read the ancient gravestones beneath our feet. People died younger then, and so the epitaphs are often poignant. One family lost six children in infancy, all buried here. Another listed three sons, ranging in age from 11 years to 11 months. Typically, whether they are old or young, the people memorialized inside these churches were wealthy, since they had the money to afford a place in a city center church and an expensive tombstone. That’s why I stopped short when I came across the grave of Richard James Said.

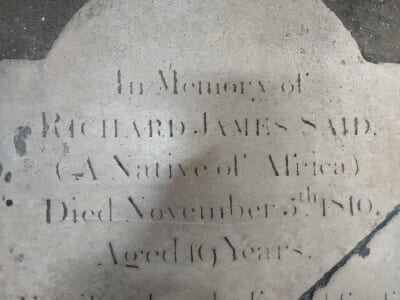

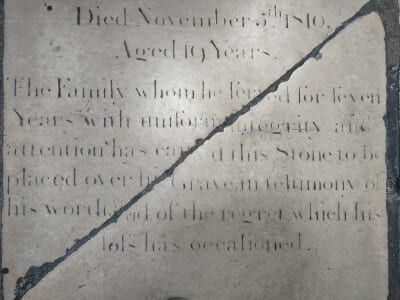

The stone reads “In Memory of Richard James Said, (A Native of Africa) Died November 5th, 1810, Aged 19 Years. The Family whom he served for seven years with uniform integrity and attention has caus’d this Stone to be placed over his Grave in testimony of his worth and of the regret which his loss has occasioned.” I stopped short. It’s rare to find direct acknowledgment of slavery in the heart of the British Empire. And here we were, mere steps from Trafalgar Square, witnessing this history carved in stone. I wish I knew this young man’s story. What caused his death at the age of 19? Was he really a “Native of Africa,” born in Africa and brought over on a slave ship just a few short years before the British abolished the slave trade (but not the practice of slavery) in 1807? He was just 12 years old when he began his so-called “service” to the unnamed family. The expensive tombstone suggests that he was valued and hopefully (though not necessarily) treated well by his owners, but the very fact that they owned a human being at a time when public opinion in Britain was beginning to shift against the slave trade tells another story.

I went home and Googled Richard James Said, hoping that a historian could tell me his story but all that came up was a record of the tombstone, a record that didn’t even contain the full text written on the grave. To have any sort of record of the life of an enslaved person is rare enough. Like the US, the UK would rather erase some parts of its past, to forget that young men like Richard James Said were once bought and sold in the middle of our supposedly civilized cities.